Zero-copy (de)serialization

Introduction

Apache Iggy considers performance as one of its core principles. We take pride in being blazingly fast, as proof of that, we have made benchmarking first-class citizen.

Zero-copy schema was a natural next step in our high-performance journey, it was part of our roadmap for quite a while, until the day we have finally merged it. In this blog post, we will share our path to implementing it.

Zero copy with rkyv

Our initial approach to zero copy was leveraging the existing rkyv package which might or might not have been the best choice (more about it later). Using rkyv is pretty straightforward, as it revolves around three traits (Archive, Serialize, Deserialize), all three of which can be derived using derive macros, thus making our job pretty easy.

#[derive(Archive, Deserialize, Serialize)]

struct IggyBatch {

pub start_offset: u64,

pub start_timestamp: u64,

pub end_offset: u64,

pub end_timestamp: u64,

pub batch_size: u64,

pub attributes: u16,

pub messages: Vec<IggyMessage>,

}

Same traits are derived for IggyMessage

#[derive(Archive, Deserialize, Serialize)]

pub struct IggyMessage {

pub offset: u64,

pub timestamp: u64,

pub value: Vec<u8>,

pub headers: Vec<u8>,

}

Rkyv internally figures out the memory layout used for serialization, such that it can later on cast it back into its Archived form. (A couple bits of trivia: rkyv, when performing zero copy deserialization, turns the byte representation of your data into its Archived form, so instead of IggyBatch we receive ArchivedIggyBatch, rkyv has to reimplement certain complex types such as Vec, HashMap etc., and that’s why it yields back your type in Archived form.)

You can learn more about it by reading the rkyv book, or from this presentation.

After a further evaluation of IggyBatch, we found that while it was good enough, there was still room for improvement.

Imagine a scenario where the client sends a batch with 100 messages, the server receives it, turns it into Archived form, updates metadata fields, caches/persists it and sends an ack back to the client. The client sends a fetch request for 10 messages, the server receives the request, peeks into the cache, finds our batch of 100 messages and here is the tricky bit -

We would like to send back only a slice of the cached data (10 messages instead of 100), but due to rkyv's memory layout, one cannot simply take a slice of those bytes and perform the transformation into its Archived form.

So rather than deriving rkyv's traits to IggyBatch, we decided to refine our approach by working at the individual message level.

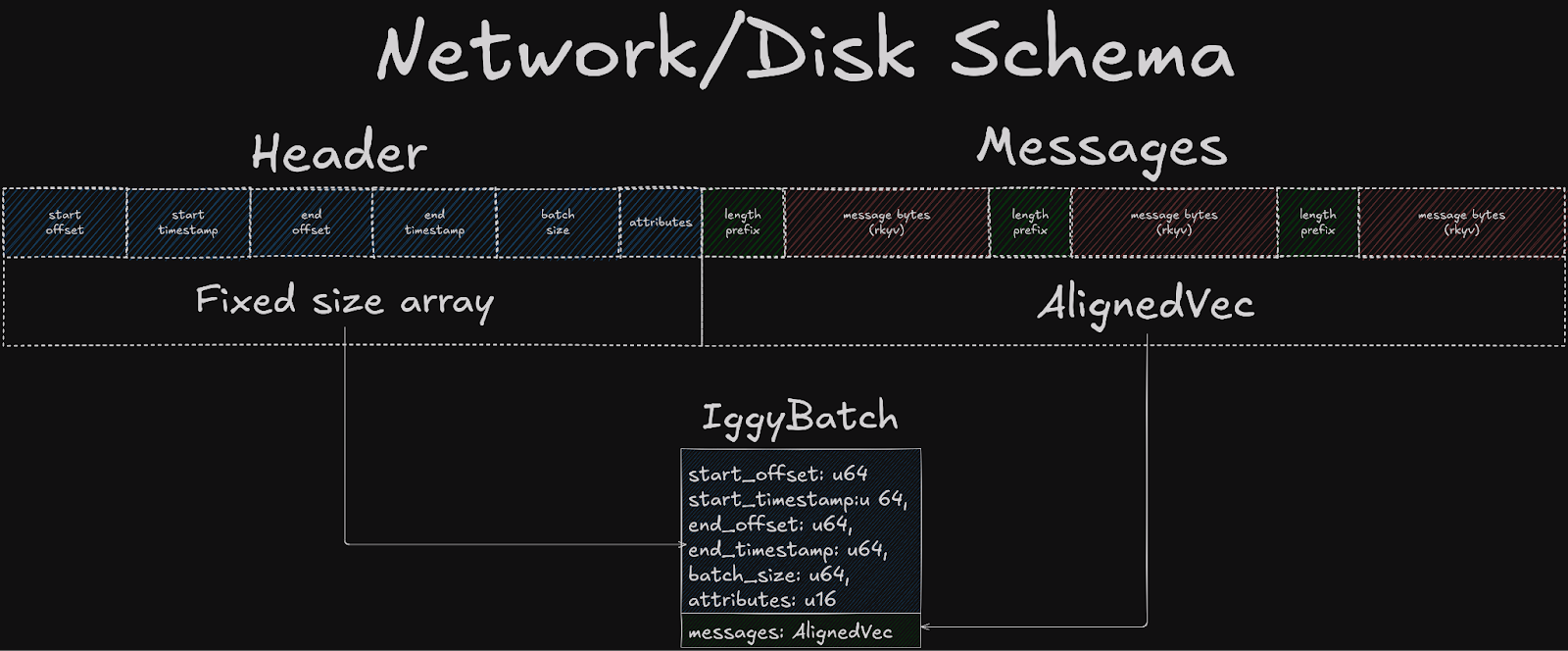

struct IggyBatch {

pub start_offset: u64,

pub start_timestamp: u64,

pub end_offset: u64,

pub end_timestamp: u64,

pub batch_size: u64,

pub attributes: u16,

pub messages: AlignedVec, // AlignedVec is custom type from rkyv, that represents a vector of bytes.

}

We redesigned the IggyBatch structure so that the messages field now stores a byte representation of Vec<IggyMessage>, with each message prefixed by its 4-byte length. This approach allows us to traverse through the data, cast individual messages to its archived form, and perform some work on it.

By creating this frankenstein layout that combines length prefixes with rkyv's memory layout, we've achieved the flexibility that we were aiming for, optimized for the most costly copies (messages), rather than the entire batch including its header.

One thing worth noting, rkyv requires buffer with your data to be aligned, going after rkyv book - “16-aligned memory should be sufficient.”, thus if you want to prefix your payload with any metadata, make sure that it doesn’t misalign your buffer, or you can opt-in the unaligned feature.

Beyond rkyv

Rkyv is a pretty “heavy” crate that spreads through your entire application from network schema to disk schema, partially coupling your own versioning with its. For many applications there is no way around this, as it is the most complete zero-copy deserialization crate, but we decided to implement a more lightweight solution that gives us control over the memory layout.

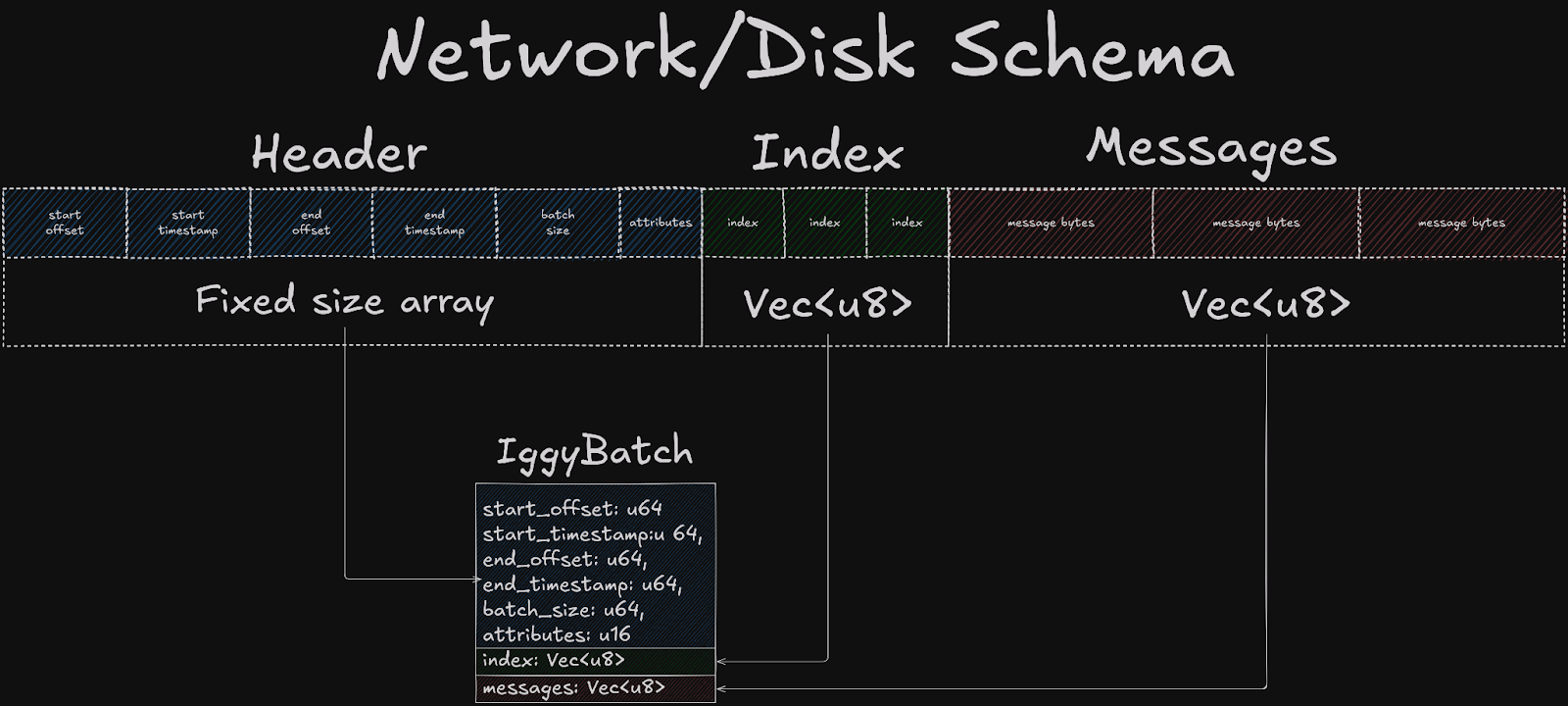

We’ve decided to still process messages individually, but have replaced length prefixes with a separate index vector.

pub struct IggyBatch {

// Remaining fields...

pub indexes: Vec<u8>,

pub messages: Vec<u8>,

}

This index vector consists of bytes that, when deserialized form u32 values that point to specific positions within the message data. Separating messages from indexes serves purpose beyond the scope of this blog post, but shortly, this index structure closely resembles what we use on the server for message lookup in the log. This in turn, later on allows us to efficiently reuse memory.

When iterating through the batch, we yield views instead of fully deserialized messages.

In case if we’d need to have IggyMessage deserialized, we can do it just in time, rather than eagerly, for example when client processes a fetched batch from the server.

This approach allows us to combine the flexibility of solution with length prefixes using rkyv as well as having the freedom of not depending on a 3rd party crate, in fact this solution looks fairly similar to serde partial zero copy deserialization.

Benchmarks

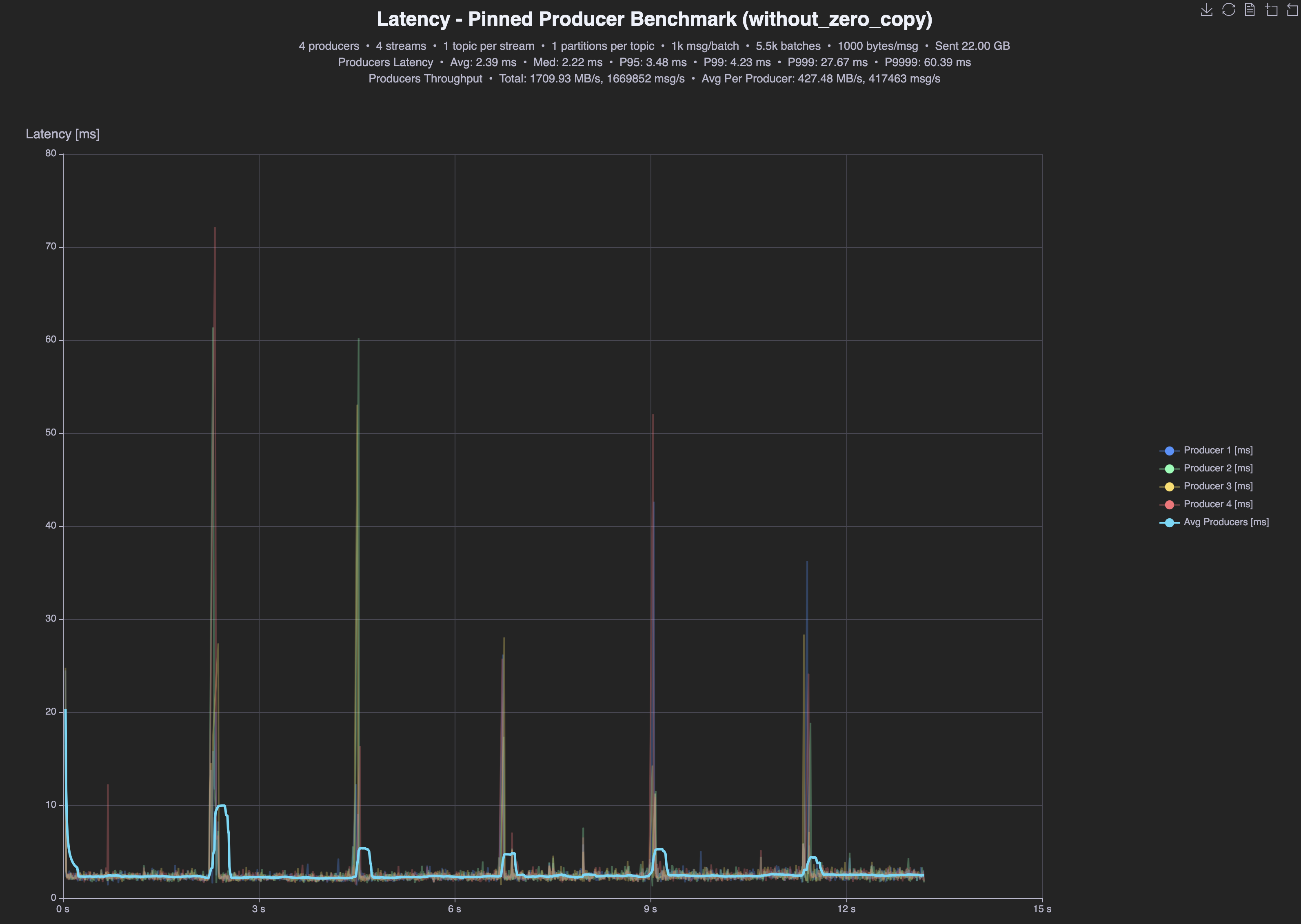

Now the part that all of you are probably most interested in - le benchmarks.

Those results come from an AWS i3en.3xlarge instance

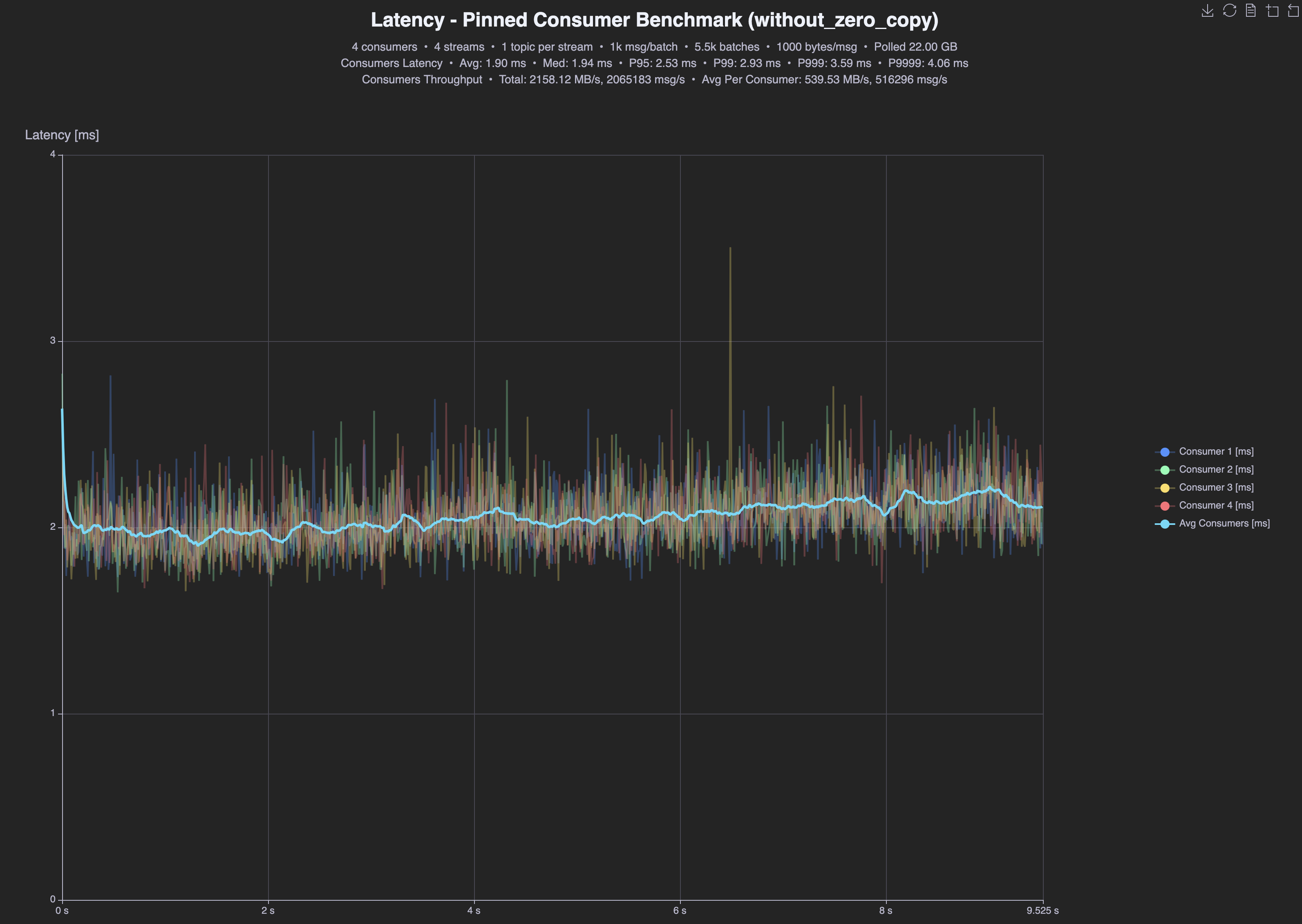

Before

| No zero-copy | tput | p95 | p99 | avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Producer | 1.7GB/s | 3.48ms | 4.23ms | 2.39ms |

| Consumer | 2.1GB/s | 2.53ms | 2.93ms | 1.90ms |

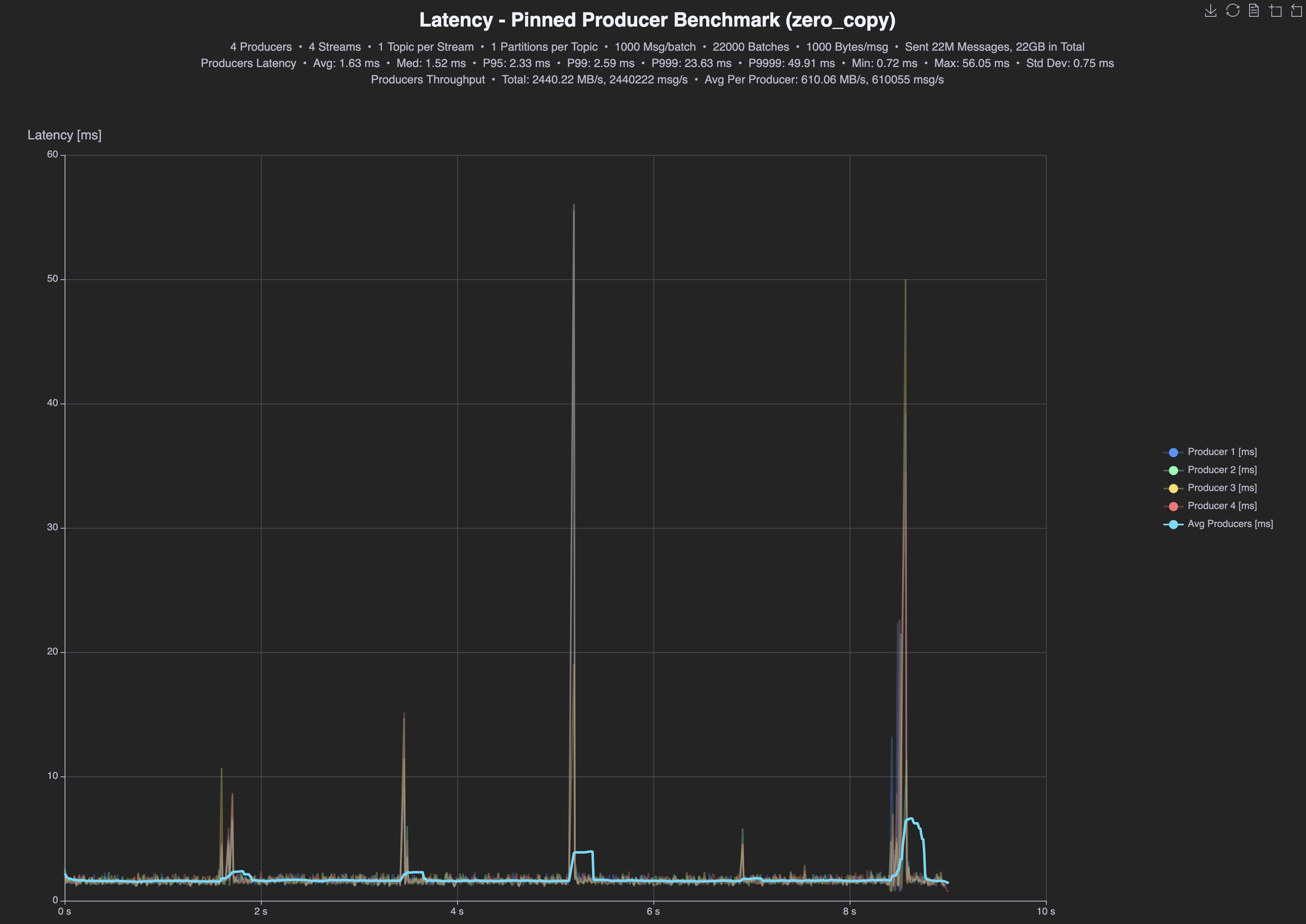

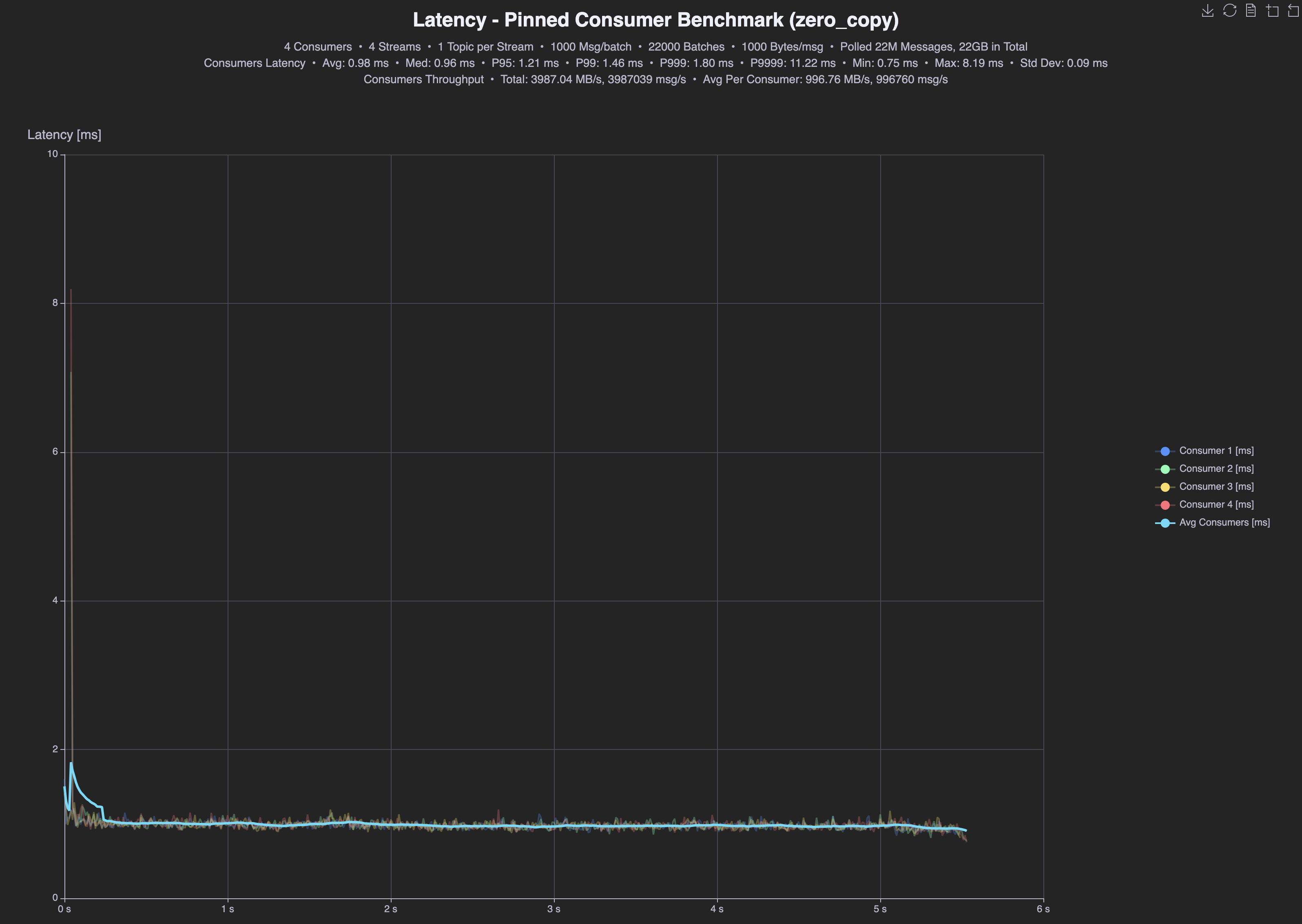

After

| Zero-copy | tput | p95 | p99 | avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Producer | 2.4GB/s | 2.33ms | 2.59ms | 1.63ms |

| Consumer | 4.0GB/s | 1.21ms | 1.46ms | 0.98ms |

Almost 2 times higher throughput for reads (2,1GBps vs 4GBps), 40% higher throughput for writes (2,4GBps vs 1,7GBps), 2x better p99 latencies for reads (2.93ms vs 1,46 ms) and 63% better p99 latencies for writes (4.23ms vs 2.59ms).

You can find more detailed comparisons on our benchmarking website.

Concluding

It was a lot of fun exploring the entire design space for our zero copy schema. Depending on the constraints one might end up with a completely different solution, in fact zero copy isn't always the optimal approach, for example, if you'd like to read more about challenges that folks in embedded development have to overcome, check out this Bluesky post from James Munns, or more broadly his project postcard-rpc.

What’s next for Iggy

Implementing zero-copy was a major milestone for us, but the train doesn’t slow down. Next in line is io_uring and thread per core shared nothing architecture. We’ve already promised that we will publish more details about it once we have the results from our benchmark tests, so expect a highly technical blog post in near future.

For now we did a proof of concept long time ago, but realised a few things along the way that we would like to do differently. So we will. Iggy moves onward and upward! 🚀